From Web to Living Room: Porting to Apple TV

If you read the first part of this story, you know how Debug Survivor went from a single prompt to a playable browser game, then to the iOS and Android app stores over a weekend. Capacitor made that possible… it wraps your web app in a native container, and suddenly you're shipping to mobile.

So the obvious question was: could I do the same thing for TV?

How I ported a React application to a native Swift game and shipped to Apple TV without knowing Swift—or React for that matter.

If you read the first part of this story, you know how Debug Survivor went from a single prompt to a playable browser game, then to the iOS and Android app stores over a weekend. Capacitor made that possible… it wraps your web app in a native container, and suddenly you're shipping to mobile.

So the obvious question was: could I do the same thing for TV?

Why Go Native?

My first thought was to use Capacitor again. It wrapped the web app for iOS and Android — surely tvOS would be similar?

No. Apple doesn't allow browsers on Apple TV. There's no WebKit. No WebView. No way to run JavaScript in a native container. If you want an app on the big screen, you write Swift.

Here's the thing: I've never written a line of Swift in my life.

So the question became: could I orchestrate an AI to rewrite an entire game in a language I don't know, from a framework I don’t know, for a platform I've never developed for?

The 40-Hour Estimate

Before starting, I asked Claude to generate a porting plan. The result was comprehensive: six phases covering project setup, player movement, weapon systems, enemy spawning, UI, bosses, and tvOS-specific polish.

The estimate? 40 hours. One week of full-time work.

Feature Parity

The web version had grown into a proper game.

Matching it meant implementing:

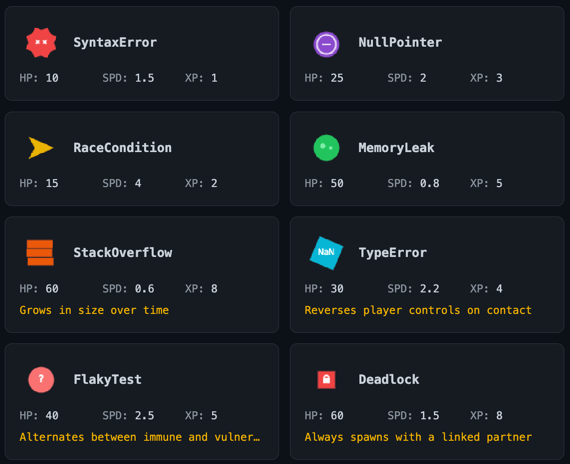

9 enemy types

8 bosses

18 weapons

Elite modifiers

PR Events

Hazard systems

Then there was tvOS-specific work:

Siri Remote support: The touch surface maps to a virtual D-pad

Gamepad support: Xbox and PlayStation controllers work via Apple's GameController framework

Top Shelf image: A 1920x720 banner that displays when your app is highlighted on the home screen

Focus engine: SwiftUI menus need to support the tvOS focus system for remote navigation

And then there was the app icon…

The LSR Rabbit Hole

tvOS app icons aren't images. They're layered stacks that create a 3D parallax effect when you hover over them with the remote. Apple requires a specific file format called LSR (Layered Still Resource).

I had never heard of this format.

Getting a working layered icon took longer than implementing several weapons combined. It's a perfect example of platform friction that no amount of AI assistance can bypass; you just have to fight with the tooling until it works.

The AI Collaboration Pattern

As I said before: I don't know Swift. I don't know React either. The entire Debug Survivor project—web, mobile, and tvOS—was built through AI orchestration.

For the tvOS port, this meant:

Reading code I don't understand: I'd look at the TypeScript renderer and identify what it was doing conceptually, even if I couldn't write it myself

Describing behavior, not implementation: "The SyntaxError enemy is a red spiky circle with 8 triangular points that rotates continuously" rather than "convert this arc() call"

Testing relentlessly: Since I couldn't code review the output, I had to run it and see if it worked

Reporting symptoms: "Players die immediately after selecting a level-up upgrade" and letting the AI diagnose the cause

The AI generated 9 detailed planning documents over the course of development—boss fixes, feature parity checklists, bug triage lists. Each one was a checkpoint where I'd review what was broken, approve a fix strategy, and watch it execute.

What still required human judgment:

Game feel: Is 45-60 seconds between LAG_SPIKE hazards too frequent? (Yes. We changed it.)Visual verification: Does this enemy look right? Does the game feel responsive?

What I Learned

You don't need to know the language. I shipped a Swift app without knowing Swift. The barrier isn't syntax; it's knowing what you want and being able to describe it. If you can play a game and articulate "this doesn't feel right because X," you can direct an AI to fix it.

Platform friction is still real. AI can write Swift. AI cannot fight Xcode's asset catalog. The LSR file format, provisioning profiles, and App Store screenshot requirements. These are bureaucratic obstacles that require human patience.

Testing replaces code review. When you can't read the code, you have to run the code. I tested obsessively. Every change, every fix, every new feature: run it, play it, break it. The feedback loop was: describe problem → AI proposes fix → test → repeat.

Debugging is collaborative. I couldn't diagnose the level-up death bug by reading code. But I could describe the symptom precisely: "Player dies the instant I select an upgrade, every single time, even with no enemies nearby." The AI hypothesized the deltaTime spike. We were both necessary.

Try It Yourself

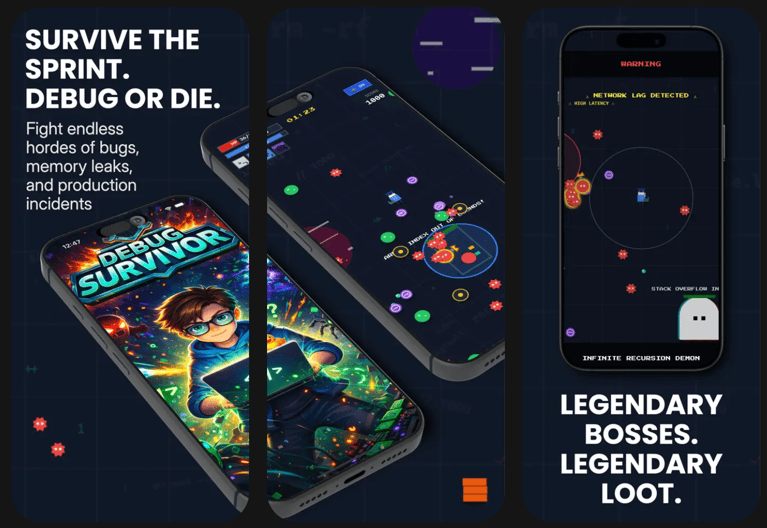

Debug Survivor is now live on three four platforms:

From a single prompt to four platforms. The browser version in 20 seconds. Mobile in 24 hours. Native tvOS in 26 hours.

The total time from "I wonder if AI can build a game" to shipping on web, iOS, Android, and Apple TV: about a week.

This whole project started as a test. Could I take a dumb idea and ship it? Could I use AI to build something real, not just a demo? Turns out: yes.

But more than that… it was fun. Watching the pieces come together, hunting down bugs through pure observation, seeing the game run on my TV for the first time. There's something deeply satisfying about orchestrating something into existence.

I don't know what I'll build next. But I know the process works. And I know I'll enjoy finding out.

From Prompt to App Store in 48 Hours

It started with a single sentence prompt: "Vampire survivors style game where you fight programming bugs." 48 hours later, the game was live on the App Store. This is the story of how I used AI as my implementation partner and Capacitor as my cheat code to ship a complete mobile game in a single weekend.

How I built a complete mobile game using AI and shipped it to the App Store over a weekend.

It started with a single prompt:

"Vampire survivors style game where you fight programming bugs."

That was it. That was the whole prompt I fed into Google’s AI Studio. Twenty seconds later, I was looking at a playable browser game where I was shooting syntax errors at a boss named Robert'); DROP TABLE Students;--. By the end of the weekend, that same game was live on the App Store.

The Spark: Curiosity and Momentum

I didn't sit down on Friday night with a grand plan to ship a game. I just had a persistent idea and wondered if Google's Gemini model could actually build it. I expected a half-broken mess, but twenty seconds later, I was looking at a playable browser game.

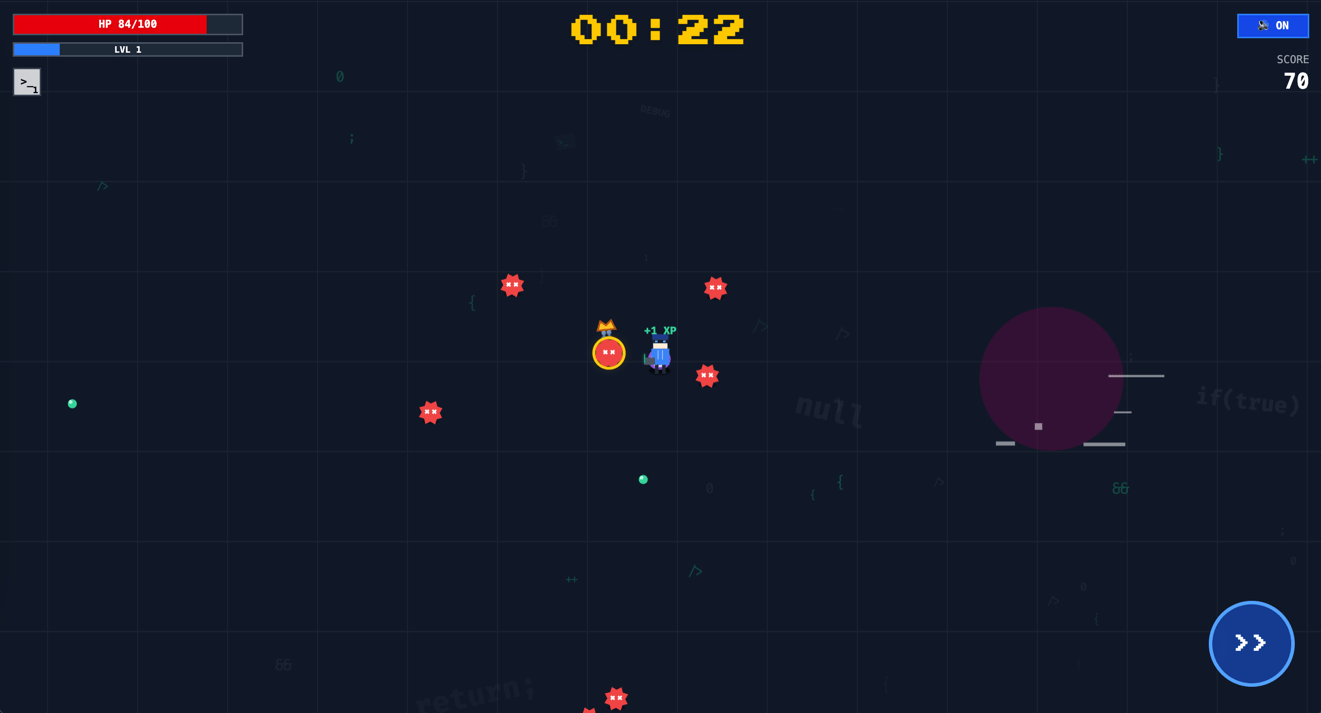

It was a simple React app using the Canvas API, but it had the fundamentals: a player character, enemies that moved, a basic weapon, and XP gems. It wasn't polished, but it was playable.

That's the moment where most side projects fail—the gap between the idea and the first working line of code. By skipping that gap entirely, I found myself in a loop I hadn't experienced before. I liked what I saw, so I gave it another requirement. Then another. I wasn't "developing" in the traditional sense; I was chasing the momentum of seeing a dumb idea become real in real-time. Each prompt was a tiny dopamine hit of progress.

The First Hour: Rapid Iteration

The initial prototype had problems. The player was a generic circle. Enemies were squares. The balance was nonexistent—you'd get overwhelmed in seconds.

But here's what made AI-assisted development different: fixing these issues wasn't a multi-day effort. It was a conversation.

"Add floating XP text when gems are collected."

"The yellow enemies are impossible to defeat... make them spawn less often."

"Implement a player dash ability with a cooldown."

Each request came back as working code within seconds. I wasn't debugging—I was directing. The AI handled the implementation details while I focused on game feel.

Within the first hour, the game had:

A proper developer character with a laptop and hoodie

Multiple enemy types with unique behaviors (Stack Overflow bugs that grow larger, Type Error bugs that reverse your controls)

A weapon upgrade system during level-ups

Screen shake effects

A dash mechanic with invulnerability frames

The Hallucination Hurdle

It wasn't all magic. By Friday night, the codebase was a single 2,000-line file. Every time I asked the AI to add a new weapon, it would get confused by the file size and accidentally "optimize" the code by deleting the enemy rendering logic.

I spent an hour wondering why my enemies had turned invisible before I realized the AI was hallucinating a "cleaner" version of the code that didn't actually work.

The fix was old-fashioned software engineering: I had to stop the feature development and ask the AI to refactor the code into separate modules—Enemy, Weapon, Renderer, etc. Once we broke the context window limits, the "amnesia" stopped. It was a stark reminder that AI is a junior developer: fast, enthusiastic, but needs supervision.

The Design Philosophy: Programming Humor as Gameplay

Early on, I realized the game's theme wasn't just aesthetic—it could inform actual mechanics. Every weapon became a programming joke that also made sense as gameplay:

Console.log() is your starting weapon because that's what every developer reaches for first when debugging. It's basic, reliable, everywhere.

Unit Test Shield orbits your character protectively. Because good tests protect your code from regressions.

Garbage Collector is an area-of-effect pulse. It cleans up everything around you, just like memory management.

Refactor Beam pierces through multiple enemies. Because a good refactor cuts through accumulated technical debt.

The enemies followed the same logic. NullPointer enemies are fast but fragile—they crash quickly. Memory Leak enemies are slow tanks that just won't die. Race Condition enemies move erratically because you never know where they'll be next.

This thematic consistency made the game more fun to build and more memorable to play.

The Boss Problem

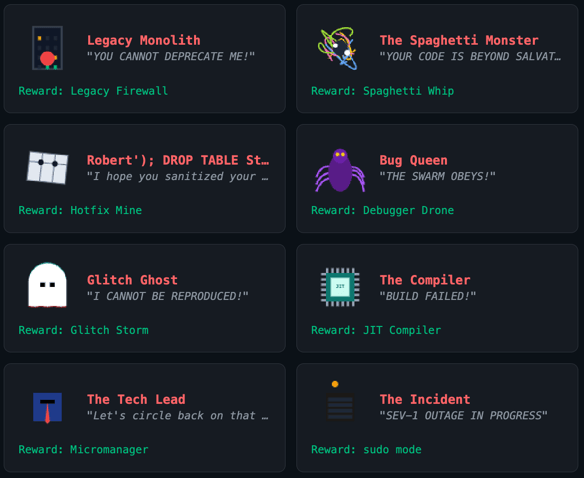

Simple enemies were working, but the game needed punctuation. Something to break up the endless horde.

Bosses became the answer, and they became the game's personality.

The Spaghetti Monster spawns obstacles across the arena, slowly making it "unreadable"—just like actual spaghetti code.

The Compiler periodically freezes your character while displaying "Compiling Assets..." Then, in phase two, it permanently deletes your lowest-level weapon from your inventory. Brutal, but thematically perfect.

Robert'); DROP TABLE Students;-- (yes, that's the actual name) attacks with SQL injection projectiles. Because of course it does.

The Incident is a burning server rack that pops up system error modals you have to dismiss. It interrupts your gameplay at the worst possible moments, exactly like a 2 AM production incident.

My favorite is The Tech Lead. It's protected by Junior Dev minions that buff it. You can't damage the boss until you deal with the juniors first. It teaches priority management through game design.

The Mobile Question

After a day of iterating on the browser version, I had something I was genuinely proud of. The game had depth. It had personality. It had the kind of "one more run" compulsion that marks a good roguelike.

Then came the thought: could this be a mobile app?

The honest answer was that I had no idea. I'd never shipped anything to the App Store. The process seemed intimidating—certificates, provisioning profiles, screenshot requirements, review guidelines. It felt like a completely different discipline.

But I'd come this far by not overthinking. Why stop now?

The Technology Decision

I spent time researching mobile development options. The choices seemed to boil down to:

React Native would let me reuse some React knowledge, but the graphics stack was completely different

Flutter had excellent performance but required learning Dart and rewriting everything

Native development was obviously the best quality but also obviously the most time-consuming

Or… Capacitor.

Capacitor wraps existing web applications in a native container. Your Canvas code, your Web Audio API calls, your touch handlers—they all just work. The wrapper provides access to native features like haptic feedback and proper fullscreen handling.

The promise was compelling: 95%+ code reuse with a 1-3 week timeline instead of 3-9 months. The catch was that some users might notice it wasn't truly native—slight loading differences, minor touch latency in the WebView.

For a game that was already running smoothly at 60fps in the browser? Worth trying.

The 24-Hour Sprint: From Browser to App Store

The actual mobile conversion happened in a blur.

Friday Night: The Prototype. I had the core loop working in the browser. It was ugly, but fun.

Saturday Morning: I installed Capacitor. Within an hour, I had the web app running on my iPhone. I added a virtual joystick because keyboard controls don't exist on phones.

Saturday Afternoon: I fixed audio issues on iOS, handled the notch on newer iPhones, and added haptic feedback. This is where the game went from "web port" to "mobile game."

Saturday Night: I used The App Launchpad to generate screenshots because I wanted something that stood out. I generated an icon, filled out the forms, and hit "Submit" before I went to sleep.

Monday: Live. The game was approved and on the store 36 hours later.

Application screenshots generated by The App Launchpad

What Made This Possible

Looking back, several factors converged to make this weekend project viable:

AI as implementation partner. I didn't need to know how to implement screen shake effects or chain lightning weapons. I needed to know what I wanted, and the AI handled the how. This freed me to focus on game design rather than technical implementation.

The browser as prototype platform. Building for web first meant instant feedback. No compile times, no simulator launches. Just save and refresh. By the time I went mobile, the game design was already validated.

Capacitor as bridge technology. Being able to wrap an existing web app rather than rewriting it made the mobile timeline reasonable. A weekend instead of months.

Iteration over planning. Every feature emerged from playing the game and noticing what was missing. The Type Error enemy that reverses your controls? That came from a prompt about "enemies with unique behaviors." The Pull Request event system that pauses gameplay for decisions? That was added to break up the monotony of endless waves.

What’s Next?

If I were to keep iterating on Debug Survivor, there are a few features at the top of my list:

The Bestiary: An unlockable index of every bug you’ve encountered. You’d start with blank entries and slowly fill them in as you "document" the bugs by defeating them.

Game Center Integration: Adding global leaderboards so developers can compete for the title of "Senior Debugger."

Achievements: Rewarding players for specific feats, like "Legacy Code" (surviving 10 minutes with only starting weapons) or "Production Hero" (defeating a boss during a simulated 2 AM incident).

Try It Yourself

Debug Survivor is available on the App Store and Google Play (Looking for testers! Invite here). It’s $2.99, though I’m running a $0.99 sale for the first month. The web version is still up at debug-survivor.leek.io.

To be clear: the goal isn’t to get rich off a weekend project. It’s about the satisfaction of taking a single prompt and seeing it all the way through to a store listing.

One sentence can become a game. That game can ship to the App Store. You can do this in a weekend.