From Web to Living Room: Porting to Apple TV

If you read the first part of this story, you know how Debug Survivor went from a single prompt to a playable browser game, then to the iOS and Android app stores over a weekend. Capacitor made that possible… it wraps your web app in a native container, and suddenly you're shipping to mobile.

So the obvious question was: could I do the same thing for TV?

How I ported a React application to a native Swift game and shipped to Apple TV without knowing Swift—or React for that matter.

If you read the first part of this story, you know how Debug Survivor went from a single prompt to a playable browser game, then to the iOS and Android app stores over a weekend. Capacitor made that possible… it wraps your web app in a native container, and suddenly you're shipping to mobile.

So the obvious question was: could I do the same thing for TV?

Why Go Native?

My first thought was to use Capacitor again. It wrapped the web app for iOS and Android — surely tvOS would be similar?

No. Apple doesn't allow browsers on Apple TV. There's no WebKit. No WebView. No way to run JavaScript in a native container. If you want an app on the big screen, you write Swift.

Here's the thing: I've never written a line of Swift in my life.

So the question became: could I orchestrate an AI to rewrite an entire game in a language I don't know, from a framework I don’t know, for a platform I've never developed for?

The 40-Hour Estimate

Before starting, I asked Claude to generate a porting plan. The result was comprehensive: six phases covering project setup, player movement, weapon systems, enemy spawning, UI, bosses, and tvOS-specific polish.

The estimate? 40 hours. One week of full-time work.

Feature Parity

The web version had grown into a proper game.

Matching it meant implementing:

9 enemy types

8 bosses

18 weapons

Elite modifiers

PR Events

Hazard systems

Then there was tvOS-specific work:

Siri Remote support: The touch surface maps to a virtual D-pad

Gamepad support: Xbox and PlayStation controllers work via Apple's GameController framework

Top Shelf image: A 1920x720 banner that displays when your app is highlighted on the home screen

Focus engine: SwiftUI menus need to support the tvOS focus system for remote navigation

And then there was the app icon…

The LSR Rabbit Hole

tvOS app icons aren't images. They're layered stacks that create a 3D parallax effect when you hover over them with the remote. Apple requires a specific file format called LSR (Layered Still Resource).

I had never heard of this format.

Getting a working layered icon took longer than implementing several weapons combined. It's a perfect example of platform friction that no amount of AI assistance can bypass; you just have to fight with the tooling until it works.

The AI Collaboration Pattern

As I said before: I don't know Swift. I don't know React either. The entire Debug Survivor project—web, mobile, and tvOS—was built through AI orchestration.

For the tvOS port, this meant:

Reading code I don't understand: I'd look at the TypeScript renderer and identify what it was doing conceptually, even if I couldn't write it myself

Describing behavior, not implementation: "The SyntaxError enemy is a red spiky circle with 8 triangular points that rotates continuously" rather than "convert this arc() call"

Testing relentlessly: Since I couldn't code review the output, I had to run it and see if it worked

Reporting symptoms: "Players die immediately after selecting a level-up upgrade" and letting the AI diagnose the cause

The AI generated 9 detailed planning documents over the course of development—boss fixes, feature parity checklists, bug triage lists. Each one was a checkpoint where I'd review what was broken, approve a fix strategy, and watch it execute.

What still required human judgment:

Game feel: Is 45-60 seconds between LAG_SPIKE hazards too frequent? (Yes. We changed it.)Visual verification: Does this enemy look right? Does the game feel responsive?

What I Learned

You don't need to know the language. I shipped a Swift app without knowing Swift. The barrier isn't syntax; it's knowing what you want and being able to describe it. If you can play a game and articulate "this doesn't feel right because X," you can direct an AI to fix it.

Platform friction is still real. AI can write Swift. AI cannot fight Xcode's asset catalog. The LSR file format, provisioning profiles, and App Store screenshot requirements. These are bureaucratic obstacles that require human patience.

Testing replaces code review. When you can't read the code, you have to run the code. I tested obsessively. Every change, every fix, every new feature: run it, play it, break it. The feedback loop was: describe problem → AI proposes fix → test → repeat.

Debugging is collaborative. I couldn't diagnose the level-up death bug by reading code. But I could describe the symptom precisely: "Player dies the instant I select an upgrade, every single time, even with no enemies nearby." The AI hypothesized the deltaTime spike. We were both necessary.

Try It Yourself

Debug Survivor is now live on three four platforms:

From a single prompt to four platforms. The browser version in 20 seconds. Mobile in 24 hours. Native tvOS in 26 hours.

The total time from "I wonder if AI can build a game" to shipping on web, iOS, Android, and Apple TV: about a week.

This whole project started as a test. Could I take a dumb idea and ship it? Could I use AI to build something real, not just a demo? Turns out: yes.

But more than that… it was fun. Watching the pieces come together, hunting down bugs through pure observation, seeing the game run on my TV for the first time. There's something deeply satisfying about orchestrating something into existence.

I don't know what I'll build next. But I know the process works. And I know I'll enjoy finding out.

Dotfiles for Developers — Part 2

In Part 1 of this series, we discussed setting up your machine with a basic toolset using Homebrew and Oh My Zsh. I highly recommend checking it out before beginning here (if you haven’t already).

Homebrew Cask

Homebrew is great for installing essential command line tools and terminal software — but it can also be used to install most Mac apps as well! Using Homebrew to install your most used Mac apps can be a great way to quickly reinstall (and keep up to date) the apps running on your system.

Let’s say you wanted to install the Spotify app on your system using Homebrew. You can search for software by using the brew search command:

$ brew search spotify

==> Formulae

spotify-tui spotifyd

==> Casks

mutespotifyads spotify spotify-now-playingIn this example, you will see that our search returned 2 Formulae for Spotify related CLI tools and 3 Casks for apps that can be installed. Since we are trying to install the Spotify app, we just need to brew install it:

brew install spotifyThat’s it! Now the Spotify app is installed and ready to use.

This will come in handy when we combine this with Homebrew Bundle (below) to automate the installation of all of our installed software.

Mac App Store

If you have software located in the Mac App Store that you would like to automate or install via the command line — then you will need to install a tool called mas-cli:

brew install masEach application in the Mac App Store has a product identifier which is also used for mas-cli commands. Using mas list will show all of your currently installed applications and their product identifiers:

$ mas list

441258766 Magnet (2.5.0)

969418666 ColorSnapper2 (1.5.1)

465965038 Markdown Pro (1.0.9)

429449079 Patterns (1.2)You can search for software using mas search in order to return the matching identifier for the software you want to install:

$ mas search twitter

1482454543 Twitter (8.62)… and then install using mas install:

mas install 1482454543Homebrew Bundle

Homebrew comes with a really useful tool for setting up new machines called Homebrew Bundle. If you are familiar with Composer’s composer.json or NPM’s package.json, then you will feel right at home with how Bundle functions. Homebrew Bundle uses a Brewfile that defines everything required to reinstall your whole Homebrew setup — including any installed software, casks, taps, and even fonts!

If you have been using Homebrew for awhile, you may already have many things installed and configured to your liking. You can generate a Brewfile of everything you have previously installed by running:

brew bundle dump

You can then use the generated Brewfile to reinstall everything on your system as it was previously by running the following:

brew bundle install

This command will run through your Brewfile and install everything needed to get your system up and running.

Example Brewfile

Here is a small example of what a common Brewfile will look like. Additionally, this is a good starting point if you are new to installing software with Homebrew — feel free to remove anything that you don’t need:

tap "homebrew/bundle" tap "homebrew/cask" tap "homebrew/cask-fonts" tap "homebrew/core" tap "homebrew/services"brew "composer" brew "coreutils" brew "git" brew "mackup" brew "mysql" brew "node" brew "php" brew "pygments" brew "wget" brew "zsh-syntax-highlighting"cask "caffeine" cask "imageoptim" cask "kaleidoscope" cask "postman" cask "responsively" cask "slack" cask "spotify" cask "sourcetree"mas "Xcode", id: 497799835

Note: You may notice the

masline in our exampleBrewfileabove. This is because the mas-cli tool for installing Mac App Store software is integrated with Homebrew Bundle!

Mackup

Warning! As of this writing (Aug. 2024), Mackup no longer works on macOS Sonoma since it does not support symlinked preference files. Do not use until a workaround is created!

Mackup is an invaluable tool when it comes to:

Backing up your application settings to a safe directory.

Syncing your application settings among all of your workstations.

Restoring your configuration on any fresh install.

It works very simply — Mackup will backup only configuration files (no cache or temporary files) to a location of your choice and then symlink them from their original location to the backup. The default backup location is Dropbox — but you can also use Google Drive, iCloud, or any sync directory that you would like.

Example

Let’s say you would like to backup your Git configuration (.gitconfig) to Dropbox. Running mackup backup would do these things for you:

cp ~/.gitconfig ~/Dropbox/Mackup/.gitconfig rm ~/.gitconfig ln -s ~/Dropbox/Mackup/.gitconfig ~/.gitconfig

… and you can quickly restore this configuration by running mackup restore, which would do the following:

ln -s ~/Dropbox/Mackup/.gitconfig ~/.gitconfig

Installation

You can install Mackup easily with Homebrew:

brew install mackupBefore getting started, you may want to configure the Mackup backup location. To do this, create a file called .mackup.cfg in your home directory:

touch ~/.mackup.cfgIn that file — we can define our storage engine, our storage directory name, our storage path, and a few other configuration options. You should check out the documentation for more information.

In this example, we are going to backup our configuration to a ~/.dotfiles path and into a directory called mackup. Additionally, we also want to ignore the configration files for Adium and Subversion.

# ~/.mackup.cfg[storage]

engine = file_system

path = .dotfiles

directory = mackup[applications_to_ignore]

adium

subversionNote: You can get a full list of applications that Mackup supports by running

mackup list.

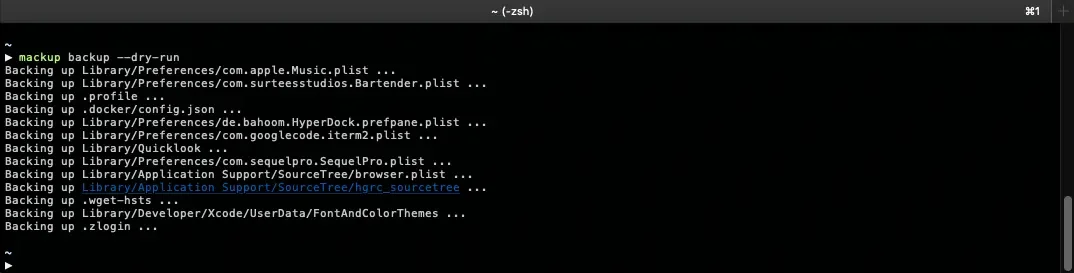

Sample terminal output showing a dry-run of Mackup.

Before we backup our system, run the following to test what Mackup will be backing up without actually executing anything:

mackup backup --dry-runThis command will show you a list of everything that will be backed up. If you see anything that you would prefer to ignore, add it to the [applications_to_ignore] section of your config file.

When you are ready, execute the same command without --dry-run:

mackup backupThat’s it! Your configuration will now be backed up to the location you specified and can be restored at any time on any machine by running mackup restore.

Custom Mackup Configurations

Mackup may not support every application that you would like to have backed up out of the box. That’s okay — it also provides an easy way to specify your own configuration files for backup.

To get started, create a .mackup folder in your home directory:

mkdir ~/.mackupLet’s say you would like to add backup support for AcmeApp to Mackup. Simply create a configuration file for the application in your ~/.mackup directory and add the files that should be backed up and synced:

touch ~/.mackup/acmeapp.cfgIn that file, you would add something similar to the following:

# ~/.mackup/acmeapp.cfg [application] name = AcmeApp[configuration_files] Library/Application Support/AcmeApp Library/Preferences/com.acme.App.plist

Mackup will now backup your custom application configuration when running mackup backup and will show your AcmeApp configuration when running mackup list.

Tip: Take a look at the configuration files of other applications supported by Mackup to get a better idea of what files they backup and how they are configured.

Oh My Zsh and Mackup

As of this writing, Mackup had to remove Oh My Zsh support in order to resolve a bug when updating. We could write our own Mackup configuration file to backup our Oh My Zsh config — but there is an easier way!

As I mentioned in Part 1 of this series, your Oh My Zsh custom scripts can be changed to any directory you’d like by setting the $ZSH_CUSTOM variable in your .zshrc file. We can use this variable to set our Mackup backup location as the directory Oh My Zsh should look for custom scripts.

Assuming we are storing our Mackup backups in ~/.dotfiles/mackup, let’s start by copying your custom Oh My Zsh scripts there:

$ mkdir -p ~/.dotfiles/mackup/.oh-my-zsh $ cp -R ~/.oh-my-zsh/custom ~/.dotfiles/mackup/.oh-my-zsh

We can now configure Oh My Zsh to look in this directory for our custom scripts by modifying our .zshrc:

# ~/.zshrc

# Would you like to use another custom folder than $ZSH/custom?

ZSH_CUSTOM=${HOME}/.dotfiles/mackup/.oh-my-zsh/custom

…and now our custom Oh My Zsh scripts are safely backed up to our Mackup sync directory and Oh My Zsh is configured to look there for them.

Conclusion

We have now covered almost everything you need to know to setup and use Homebrew and Mackup on your machine to backup your system and restore it easily. In the final part of this series, we will try to tie all of this knowledge together by backing up your configuration to your own dotfiles Git repository. The goal (again) being to be able to deploy your backup on any new machine and to get yourself up and running with your preferred development environment as quickly as possible.

Dotfiles for Developers — Part 1

This guide is tailored for developers and explains managing, configuring, and customizing your own macOS system dotfiles.

I have spent way too many hours pouring over "dotfiles" repositories on GitHub — hoping to add shortcuts or small improvements to my personal setup.

There are already plenty of resources on the web for managing and configuring your own dotfiles, but I wanted to document my own "best practices" in the hopes that someone else could possibly learn from my experience.

This guide is tailored to developers using macOS and is intended for beginners. However, my hope is that even experienced developers can pick up a few tips & tricks along the way.

Note: Dotfile configuration is extremely personal. This guide outlines my preferences but you should take inspiration from this and other resources and use the pieces that work for you.

What are dotfiles?

If you aren't familiar with dotfiles, then let's start here. Dotfiles are small configuration files found on *nix systems that allow you to customize that system based on your own personal preferences. These files usually have names that begin with a . and are thus hidden from standard directory listings.

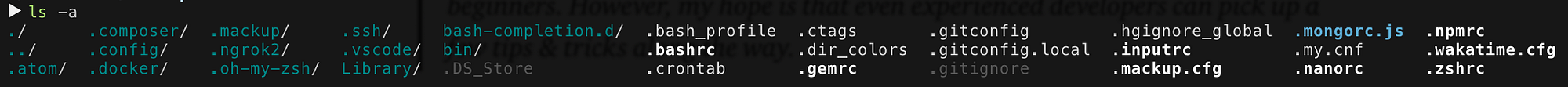

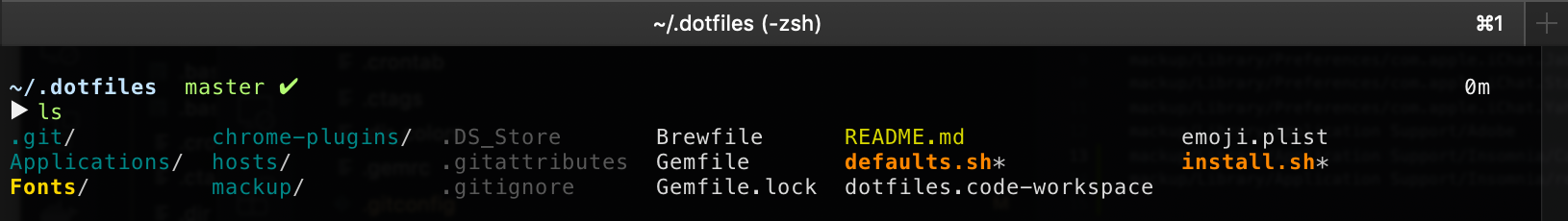

Sample terminal output showing various dotfiles.

Homebrew

Homebrew is marketed as "the missing package manager for macOS (or Linux)" and has earned its reputation as such. It is essential and is most likely the first thing any developer installs when setting up a new machine.

Homebrew allows you to easily install/update tools and even Applications from your command line interface by running brew install <formula>.

Installation

Before you can install Homebrew, you must have the Command Line Tools for Xcode installed. It includes the compilers and tools necessary to build from source. You can install it by running the following:

sudo xcode-select --install

You can then install Homebrew by running the simple installation command on the Homebrew website:

/bin/bash -c "$(curl -fsSL https://raw.githubusercontent.com/Homebrew/install/HEAD/install.sh)"

Setting Up Your $PATH

Your system $PATH is basically just a list of directories (separated by :). When you enter a command into the terminal, your system will go through those directories and look for the program that corresponds to that command.

Homebrew installs tools to /usr/local/bin by default, so you should ensure this directory is near the beginning of your $PATH.

This step is done for you on the latest versions of macOS, but it is essential for the tools installed with Homebrew to function properly. If you are on a version of macOS prior to 10.14 Mojave, run the following command to add the Homebrew installation location to your $PATH:

echo 'PATH="/usr/local/bin:$PATH"' >> ~/.bash_profile

Note: The Homebrew installation and the command above will configure your

$PATHfor Bash shells. We will be installing Zsh in the next section — and thus, we will need to configure our$PATHthere as well.

Alternatively — for advanced users — you can insert /usr/local/bin at the beginning of the file /etc/paths to change the global system default paths order (for all users/shells). The final result should look something like this:

/usr/local/bin /usr/bin /bin /usr/sbin /sbin

Common Tools

Here is a small list of common tools that I usually install with Homebrew to get you started — feel free to only install the ones you need:

# Core brew install git brew install coreutils brew install pygments # PHP brew install php brew install composer # JavaScript brew install node brew install yarn

iTerm2

Okay — so this isn't completely related to dotfiles, but I highly recommend replacing Apple's default Terminal application if you haven't already.

iTerm2 is my replacement of choice and is the one I have used for years. It is open source, extremely customizable, and comes with many useful features.

You can install it directly from the iTerm2 website, or by using Homebrew:

brew install iterm2

Tip: After installing, check out this GitHub repository of color schemes and choose one that works for you.

Zsh

Z shell (Zsh) is a Unix shell extension of Bourne shell — similar to Bash — and contains many new features and improvements:

Auto-completion: Zsh tab completion is more feature rich than Bash and allows you to navigate options with ease.

Auto-correction: Zsh is more forgiving when it comes to spelling and typos in commands by detecting errors and offering to correct them automatically.

Themes: Zsh allows complete customization of your prompt including the ability to put text on the right side of the screen.

… and many more!

Installation

Zsh is already installed on the latest editions of macOS. You should check that you have at least version 5.x (or greater) by running zsh --version. You can also choose to install the latest version using Homebrew:

brew install zsh

Note: Starting with macOS Catalina, Macs will now use Zsh as the default login shell and interactive shell across the operating system.

Oh My Zsh

Screenshot of my Oh My Zsh theme (built on the "avit" theme).

Installation

Install Oh My Zsh by running the installation command from the homepage:

sh -c "$(curl -fsSL https://raw.github.com/ohmyzsh/ohmyzsh/master/tools/install.sh)"

If it isn't already, the installation procedure will ask you if you would like to make Zsh your default shell — if it doesn't (or if you want to wait) — you can set Zsh as your default shell at any time by running the following command:

chsh -s $(which zsh)

Configuration

The default configuration that comes out of the box with Oh My Zsh is pretty good and is already a major improvement over the standard Bash shell. However, the power of Oh My Zsh is with the many customization options available. We will go over some of the basic choices — but if you want to deep dive into all of the customization options available, check out the Oh My Zsh Wiki.

The configuration file for Zsh is called .zshrc and lives in your home folder (~/.zshrc). Open it in your editor of choice and let's customize:

Setting Your Zsh $PATH

The first line of the Oh My Zsh .zshrc should let you change the shell's $PATH variable. Uncomment the export line and you are all set:

# If you come from bash you might have to change your $PATH.

export PATH=$HOME/bin:/usr/local/bin:$PATH

Theme

There are hundreds of themes to choose from, but the default Oh My Zsh theme is "robbyrussell". The Oh My Zsh Wiki page on Themes displays a list of available themes along with screenshots.

You can change the theme by looking for the line that starts with ZSH_THEME and updating it:

# See https://github.com/ohmyzsh/ohmyzsh/wiki/Themes

ZSH_THEME="avit"

Plugins

Oh My Zsh comes bundled with hundreds of plugins that you can take advantage of. Again, check out the Oh My Zsh Wiki page on Plugins to get a better idea of the plugins available to you.

You can enable any plugin by adding its name to the plugins array found in your .zshrc file. Here are some good default ones to get your started:

# See https://github.com/ohmyzsh/ohmyzsh/wiki/Plugins-Overview

plugins=(git colorize brew osx)

… and here is what mine looks like:

plugins=(git brew colorize composer docker docker-compose gulp npm osx vagrant vscode nvm laravel)

Custom Scripts

Oh My Zsh lets you customize almost anything about your configuration — startup scripts, plugins, themes, etc. — all without having to fork and create your own version.

By default, your custom scripts will live in ~/.oh-my-zsh/custom but this can be changed to any directory you'd like by setting the $ZSH_CUSTOM variable in your .zshrc file.

You can read more information about overriding plugins/themes or creating your own plugins/themes by checking out the Oh My Zsh Wiki page on Customization. For now, let's create a simple script that loads the zsh-syntax-highlighting package.

First, make sure zsh-syntax-highlighting is installed using Homebrew:

brew install zsh-syntax-highlighting

After installing some packages, Homebrew will sometimes output some extra information and installation instructions. You can review this information at any time by running brew info <formula>. For zsh-syntax-highlighting, it says something like this:

==> Caveats

To activate the syntax highlighting, add the following at the end of your .zshrc:

source /usr/local/share/zsh-syntax-highlighting/zsh-syntax-highlighting.zsh

We could just add this line to our .zshrc as Homebrew suggests — but instead, let's modularize our configuration by keeping this directive in its own custom script.

Create the file ~/.oh-my-zsh/custom/zsh-syntax-highlighting.zsh and copy in the suggested addition:

source /usr/local/share/zsh-syntax-highlighting/zsh-syntax-highlighting.zsh

Note: Oh My Zsh will load all

*.zshfiles located in~/.oh-my-zsh/customlast. You can name your custom scripts anything you would like.

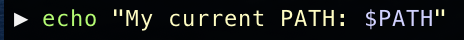

You will need to reload your Terminal for the changes to take effect. After doing so, you can test that syntax highlighting is working by typing the following command:

echo "My current PATH: $PATH"

Screenshot showing the syntax highlighting package for Zsh.

Conclusion

We've only begun to scratch the surface of what is possible with configuration, customization, and potential time savers. In the next installment of this series — we will cover adding Homebrew Bundle, Mackup, and a few other goodies to this setup to help facilitate a fully functioning backup of all dotfiles and configuration. This backup can be deployed on any new machine to get yourself up and running with your preferred development environment as quickly as possible.

Continue to Dotfiles for Developers — Part 2…

Apollo 11 Mission on Technical Debt

Back in 2009, the source code for the Apollo 11 spacecraft was transcribed from scanned images and put online for anyone to view.

The code is a true testament to programmers ability to do a whole lot with very little. More importantly, it shows that whether your end goal is to generate sales reports or fly to the moon; the programming required will largely be the same.

Here is a short snippet of code from the project (with developer comments included):

CAF TWO # WCHPHASE = 2 — -> VERTICAL: P65,P66,P67 TS WCHPHOLD TS WCHPHASE TC BANKCALL # TEMPORARY, I HOPE HOPE HOPE CADR STOPRATE # TEMPORARY, I HOPE HOPE HOPE TC DOWNFLAG # PERMIT X-AXIS OVERRIDE ADRES XOVINFLG

At some point 45 years ago, a programmer wrote and submitted this code while consciously accepting some amount of “technical debt”. Technical debt is a metaphor used to describe the eventual consequences of poor software design decisions within a codebase — or more simply — the extra development effort that is required when code that is easy to implement in the short term is used instead of applying the best overall solution.

In this metaphor, doing things the quick and dirty way sets us up with a technical debt, which is similar to a financial debt. Like a financial debt, the technical debt incurs interest payments, which come in the form of the extra effort that we have to do in future development because of the quick and dirty design choice. We can choose to continue paying the interest, or we can pay down the principal by refactoring the quick and dirty design into the better design.

Talk with any developer for a reasonable amount of time and you may hear phrases such as “bandaid fix” or “hack”. These are often good indicators that a sacrifice has been made (generally for time) and that technical debt was accrued. Additionally, you should not be surprised to find almost any codebase littered with TODO and FIXME comments — left there by developers in the hopes of someday returning to refactor.

In software development, proper care must be maintained in order to prevent accumulated technical debt from becoming a burden on a project. To keep the work flowing smoothly, teams must show special attention to paying down and preventing technical debt.

Budget for technical debt in release planning

Track technical debt in a product backlog

Ensure the Definition of Done is kept up-to-date

As an evolving program is continually changed, its complexity, reflecting deteriorating structure, increases unless work is done to maintain or reduce it.

— Meir Manny Lehman (1980)